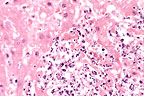

Marked hepatic necrosis in

a Tenessee walking horse. (HE, 400X, 59K)

Marked hepatic necrosis in

a Tenessee walking horse. (HE, 400X, 59K)Signalment: Equine, Tennessee Walking Horse, male, 9-years-old.

Marked hepatic necrosis in

a Tenessee walking horse. (HE, 400X, 59K)

Marked hepatic necrosis in

a Tenessee walking horse. (HE, 400X, 59K)

History: This horse had signs of diarrhea, anorexia, and weakness for one day prior to death. He would stand in one position and hold his head to one side; he then became recumbent and unable to rise.

Gross Pathology: The liver was swollen and contained numerous small white necrotic foci. The large colon had small, scattered mucosal ulcers and contained watery feces.

Laboratory Results: Listeria monocytogenes were cultured in large quantities from the liver and in small quantities from the lung. Streptococcus equi was also cultured in rare quantities from the lung. Anaerobic cultures of the liver were negative. Tests for rabies (FA and mouse inoculation) were negative.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments:

Morphologic Diagnosis and Etiology: Liver: Hepatitis, necrosuppurative, multifocal, severe, acute. Etiology: Listeria monocytogenes.

Multiple foci of hepatocellular necrosis and intense suppurative inflammation were randomly distributed throughout the liver. Gram stains revealed short gram-positive rod within the lesions. Warthin-Starry stains were negative, ruling out the presence of Bacillus piliformis.

Infection of the liver with Listeria monocytogenes is more likely to occur in fetal or neonatal lambs, calves or piglets than in adult animals. The usual route of infection is the oral route, but in mice intragastric inoculation of Listeria results in a subclinical systemic infection without causing mortality. Adult rabbits can be naturally infected with Listeria, resulting in liver lesions similar to those seen in the present case.

Factors which may limit the effectiveness of oral inoculation in mice, rats, and other mammals may be the normal gastric pH and interaction of normal intestinal microflora with Listeria. Lesions in guinea pigs could be produced only after the drastic modification of the gastrointestinal environment and microflora. The colonic ulcers observed in this horse may have allowed the systemic spread of the bacteria. In contrast to ruminants and poultry, there was no histological evidence of infection in the brain.

AFIP Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, necrosuppurative, multifocal, random, severe, with multifocal central vein thrombosis and numerous bacilli, Tennessee walking horse, equine.

Conference Note: Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive bacillus that is a commensal organism of clinically normal animals. It is present in large numbers in the feces of ruminants and is quite resistant to environmental degradation. Listeriosis most frequently occurs in ruminants and is the cause of three different syndromes: encephalitis, septicemia with visceral abscesses, and abortion. Listeria is spread by ingestion of food or water contaminated by feces, urine, placenta, or vaginal discharges from aborting animals. Listeriosis is also associated with the feeding of silage in ruminants.

Listerial encephalitis occurs most often in adult animals, especially ruminants. It is believed that the organism spreads to the brain by local invasion of cranial nerves, particularly the trigeminal nerve, rather than hematogenously. The encephalitic lesions occur predominantly in the brain stem and consist of microabscesses with central liquefactive necrosis. Acute vasculitis may develop secondary to drainage of abscesses in Virchow-Robin's space. Affected vessels may be occluded by inflammatory cells and thrombi, leading to infarction and ischemic necrosis. There is often an associated meningitis.

Aborting animals are usually not ill and abort in late gestation. Severe metritis and placentitis may be present. A distinguishing lesion of listerial abortion is necrotizing colitis with colonies of gram-positive bacilli in the aborted fetus. The fetus may also develop pinpoint abscesses in many organs including the brain, liver, kidneys, and lung.

Systemic listeriosis has been observed in neonates of several species including calves, lambs, and foals. The presence of listerial septicemia in this adult horse may indicate an underlying disease process that resulted in some degree of immunosuppression. Although many organs can be affected, multiple hepatic abscesses are the most common manifestation of systemic listeriosis. In this case, the hepatic portal areas are more severely affected, suggesting that the bacteria reached the liver via portal circulation.

Contributor: Livestock Disease Diagnostic Center, University of Kentucky, 1429 Newtown Pike, Lexington, KY 40511-1280.

References:

1. Cooper G, Charlton, B, Bickford A, Cardona C, Barton J, Channing-Santiago

S, Walker R: Listeriosis in California broiler chickens. J Vet

Diagn Invest 4:343-345, 1992.

2. Marco AJ, Prats N, Ramos JA, Briones V, Blanco M, Dominquez

L, Domingo M: A microbiological, histopathological and immunohistological

study of the intragastric inoculation of Listeria monocytogenes

in mice. J Comp Path 107:1-9, 1992.

3. Semrad SD: Septicemic listeriosis, thrombocytopenia, blood

parasitism, and hepatopathy in a llama. J Am Vet Med Assoc 204:213-215,

1994.

4. Watson GL, Evans MG: Listeriosis in a rabbit. Vet Pathol 22:191-193,

1985.

5. Jubb KVF, Huxtable CR: The nervous system in Pathology of Domestic

Animals. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, and Palmer N eds. Academic Press,

Inc., San Diego, 4th ed., vol. 1 pp. 393-397 and vol. 3 pp. 405-406,

1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #4171, 5262, 7333-5, 7475-8, 9117, 11766-80,13530-1, 18994, 20333-6, and 22770.

Signalment: 8-year-old male German Shepherd Dog.

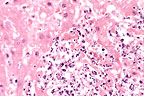

Mycotic granuloma within the

kidney of a German Shepherd dog. (HE, 200X, 106K).

Mycotic granuloma within the

kidney of a German Shepherd dog. (HE, 200X, 106K).

History: This dog had a 10 day history of decreased activity and depression. After a rabies vaccination, the dog was unable to lift its head and its hindlegs were unstable. The dog was treated for a low grade kidney infection.

Gross Pathology: At necropsy, there were multifocal and coalescing solid white nodules between 1 and 2.5 mm in diameter throughout the heart. On the capsular and cut surfaces of both kidneys there were diffusely distributed 1-2 mm white foci. In the medulla and extending in to the pelvis of the left kidney there was a 2x3 cm solid white mass. Submandibular and popliteal lymph nodes were enlarged.

Laboratory Results: The kidney was submitted for fungal culture. A light growth of a fungus was obtained. The fungus was not specifically identified because it produced sterile hyphae. Formalin-fixed tissues were submitted for histopathologic examination.

Histopathology: In sections of kidney, there was severe diffuse granulomatous interstitial nephritis with marked infiltrations of multinucleated giant cells, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes and lesser numbers of neutrophils. There was also mild to moderate fibrous connective tissue proliferation. Occasionally, cores of caseous necrosis were present within granulomas. There was also circumferential or segmental vasculitis with granulomatous exudate extending into the walls of arteries and occasionally protruding intraluminally. In PAS-stained-sections there were abundant septate fungal hyphae located primarily within multinucleate giant cells. These hyphae were consistent in morphology with Aspergillus. Comparable focal or coalescing lesions were present in the heart, spleen, multiple lymph nodes, pancreas, brain stem and cervical spinal cord.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Morphologic Diagnosis and Etiology: Nephritis, interstitial, severe and diffuse, granulomatous with intralesional septate fungal hyphae. Etiology: Aspergillus sp. (Most likely Aspergillus terreus).

Two forms of aspergillosis have been described in dogs: rhinitis and sinusitis (primarily caused by Aspergillus fumigatus) and disseminated aspergillosis. Disseminated aspergillosis is a rare disease in dogs. In essentially all cases where fungal cultures have been attempted, A. terreus has been isolated. German Shepherd Dogs were affected in 13 of 15 reported cases of disseminated A. terreus infection. The cause of the apparent predisposition of this breed has not been determined. The organism most likely gains entry via the lungs or gastrointestinal tract and spreads hematogenously. Vascular invasion is facilitated by the presence of laterally branching conidia or aleuriospores. In this case, vascular invasion was evident in the spinal cord, spleen and kidneys. Granulomatous lesions are usually widespread in this disease. The most commonly affected organs are the kidneys, heart, bone or disk spaces, liver, spleen, eye and brain.

AFIP Diagnosis: Kidney: Nephritis, granulomatous, fibrosing, diffuse, severe, with vasculitis and numerous septate fungal hyphae, German Shepherd Dog, canine, etiology consistent with Aspergillus sp.

Conference Note: Aspergillus sp. are common soil saprophytes and have a worldwide distribution. Aspergillus can be differentiated from other fungi in tissue sections by the presence of thin, parallel walls, dichotomous branching, septate hyphae, and characteristic conidiophores. These structures are best demonstrated with staining by the periodic acid Schiff procedure or silver stains.

The pathogenesis of A. terreus infection in German shepherd dogs is not known. Variations in virulence between strains of A. terreus may play a role in the establishment of infection. For example, differences in growth rates and virulence have been identified between a strain of A. terreus isolated from a case of disseminated disease in a human and saprophytic forms of the fungus. Because disseminated mycoses are commonly associated with cell-mediated immunodeficiencies in humans and other animals it is proposed that German shepherd dogs have a familial defect in some component of cell-mediated immunity; however, no evidence of immunosuppression has been found in these dogs.

Contributor: Animal Health Diagnostic Laboratory, Michigan State University, B639 West Fee Hall, East Lansing, MI 48824.

References:

1. Kabay, M.J., Robinson, W.F., Huxtable, C.R.R., and McAleer,

R. The pathology of disseminated Aspergillus terreus infection

in dogs. Vet. Pathol. 22:540-547, 1995.

2. Neer, T.M. Disseminated aspergillosis. Compendium on Continuing

Education for the racticing Veterinarian 10:465-471, 1988.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #5762, 5917, 6677-8, and 15410.

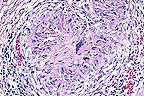

Papillary and alveolar pattern

in a canine prostatic adenocarcinoma. (HE, 200X, 107K)

Papillary and alveolar pattern

in a canine prostatic adenocarcinoma. (HE, 200X, 107K)

Signalment: 10-year-old male castrate Old English Sheep Dog.

History: This dog had a one-month history of difficult urination which terminated in inability to urinate. Rectal palpation revealed prostatic enlargement.

Gross Pathology: The prostate gland was symmetrically enlarged (5 x 3.7 x 3 cm.) and had a smooth capsular surface. Except for a cystic area filled with necrotic tissue, the prostate was palpably firm. The urinary bladder was markedly distended with urine and had numerous mucosal hemorrhages.

Laboratory Results: None submitted.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments:

Morphologic Diagnosis and Etiology: Poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma with metastases to pelvic lymph nodes; prostatic atrophy secondary to castration.

This poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma shows extensive infiltration and effacement of prostatic architecture with capsular and lymphatic invasion. Some duct-like structures lined by atrophic, metaplastic or neoplastic epithelium may still be perceived. Necrotic areas with mineralization, fibrosis and focal interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells are evident throughout the tumor.

The cause of prostatic adenocarcinoma in the dog is unknown. Such tumors develop with surprising frequency in the absence of testicular hormonal influence- at least hormones of testicular origin are not required for maintenance of these tumors. The risk of developing the disease is more that two times greater for castrated dogs as compared to intact male dogs. Immunohistochemical staining of neoplastic tissue with prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) and prostatic specific antigen (PSA) is of potential value in identifying prostatic carcinoma in dogs.

AFIP Diagnosis: Prostate gland: Adenocarcinoma, prostatic, Old English Sheepdog, canine.

Conference Note: This case was also reviewed by the Department of Genitourinary Pathology, AFIP. The prostate gland is effaced by an infiltrative, poorly demarcated mass composed of cuboidal to polygonal cells. The neoplastic cells form large nests and alveoli separated by a fine fibrovascular stroma. The alveolar structures are sometimes large and contain papillary projections of neoplastic cells and small rafts of cells within the lumens. Neoplastic cells have distinct cell borders and a moderate amount of eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. The nuclei are irregularly round with stippled chromatin and one or multiple magenta nucleoli. There is marked anisokaryosis. There is multifocal desmoplasia, as well as moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

We carefully considered transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) as a differential diagnosis. Transitional cell carcinomas frequently arise in the prostatic urethra of male dogs. Typically, urethral origin TCC forms plague like growths into the lumen of the urethra, invades the prostate gland, and obliterates the architecture. However, in this case, the presence of an alveolar-papillary pattern arising in the preexistent gland is consistent with prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Three morphologic types of prostatic adenocarcinoma have been described in the dog. Intraalveolar papillary type is the most common form and consists of large, irregularly shaped alveoli filled with papillary projections of prostatic glandular epithelium. The acinar type is the second most common form and consists of variably sized acini surrounded by a dense fibrous stroma. The rosette type is rare and is composed of alveolar structures filled with solid masses and strands of tumor cells forming rosettes.

The biologic potential is the same for all of the three forms. Prostatic carcinomas metastasize widely, most commonly to regional lymph nodes. The lung, kidneys, brain, heart, adrenal glands, spleen, liver, and skeletal tissue have also been reported as sites of metastasis for prostatic carcinoma.

Prostatic hyperplasia must be differentiated from cases of well-differentiated prostatic carcinoma. Prominent differences between the two include maintenance of the glandular architecture of the prostate with prostatic hyperplasia; in addition, hyperplastic prostatic cells are columnar and remain on the basement membrane with uniform nuclei that are basally arranged. Neoplastic cells are polygonal to round, invade adjacent stroma, and lose nuclear polarity.

Contributor: Dept. Of Vet. Diagnostic Medicine, Coll. Of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, 1333 Gortner Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108.

References:

1. Bell FW, Klausner JS, Hayden DW, et.al. Clinical and pathologic

features of prostatic adenocarcinoma in sexually intact and castrated

dogs: 31 cases (1970-1987). JAVMA 199; 1623-1630, 1991.

2. Obradovich J, Walshaw R, Goullaud E. The influence of castration

on development of prostatic carcinoma in the dog: 43 cases (1978-1985).

J. Vet. Int. Med. 1:183-187, 1987.

3. Bell FW, Klausner JS, Hayden DW, et.al. Evaluation of serum

plasma markers in the diagnosis of canine prostatic disorders.

J. Vet. Int. Med 9:149-153, 1995.

4. Nielsen SW, and Kennedy PC: Tumors of the genital systems in

Tumors in Domestic Animals. Moulton JE, ed., University of California

Press, Berkeley, 3rd ed., pp. 491-495, 1990.

5. Nikula KJ, Benjamin SA, Angleton GM, and Lee AC: Transitional

cell carcinomas of the urinary tract in a colony of Beagle dogs.

Vet Pathol 26:455-461, 1989.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #6077, and 6587.

Signalment: Alaotran gentle lemur (Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis), adult, caught in the wild in December 1990, male, euthanized May 1995.

History: After having been fed once with Russian vine (Polygonum baldschuanicum), a group of gentle lemurs developed clinical symptoms. They exhibited varying degrees of lethargy, inappetence, abdominal discomfort and diarrhea. One lemur died suddenly after 10 days and two other animals developed signs of renal insufficiency including hematuria and proteinuria, and severe uremia which was effectively managed over two to three years with antibiotic, multivitamin and anabolic steroid therapy. Early weight loss could be stopped in these two lemurs and the general physical condition improved but the animals eventually deteriorated and were euthanized due to the prognosis of terminal renal failure. The lemur presented here was euthanized three years after the onset of the first symptoms.

Gross Pathology: The animal was in a poor body condition, weighing 760g. The main pathological features were seen in the kidneys which were macroscopically very pale and had an irregular granular surface; a cortico-medullary whitish striation was visible on cut surface.

Laboratory Results: Hematuria, proteinuria, uremia. Serum creatinine: >1074 mmol/1. Blood hemoglobin: >4.7g/l. Bacteriology and parasitology of small and large intestines: negative.

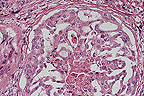

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Morphologic diagnosis: Severe chronic nephrosis with oxalate crystals. Severe diffuse fibrosis, interstitial nephritis. Etiology: Oxalate nephrolithiasis.

Histologically there was massive tubular ectasia, calcium oxalate crystals in tubular epithelium and lumen, focal atrophy of convoluted tubules with thickening of the basement membrane, sclerosis and atrophy of some glomeruli and diffuse interstitial fibrosis with mononuclear cell infiltration. Some crystals were also visible in the interstitium and were surrounded by a granulomatous reaction with giant cells. A moderate arteriosclerosis with thickening of the intima was evident in the renal arcuate arteries. Arcuatae and interlobulares and the intramural coronary arteries.

The renal histologic lesions in all three dead gentle lemurs associated with the presence of typical calcium oxalate crystals in the renal tubules, and the clinical values of both lemurs with symptoms of chronic renal failure showing high creatinine blood level, uremia, massive proteinuria and hematuria provide evidence of oxalate poisoning causing renal insufficiency.

The Russian vine Polygonum baldschuanicum belongs to the family Polygonaceae which are potentially poisonous plants do to their oxalate content. Following ingestion, soluble oxalates combine with calcium to form insoluble calcium oxalate and hypocalcemia can result, causing weakness, prostration and possibly muscle cramps and convulsions. Within a short time of ingestion of oxalate containing plants, calcium oxalate may crystallize in renal tubules, causing occlusion of the tubules, degeneration and renal failure.

AFIP Diagnosis: Kidney: Nephrosis, chronic, diffuse, severe, with tubular ectasia, interstitial fibrosis, lymphocytic interstitial nephritis, and intratubular oxalate crystals, Alaotran gentle lemur (Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis), nonhuman primate.

Conference Note: Oxalate toxicity in domestic animals occurs most commonly in sheep and cattle grazing plants high in oxalate. Toxic amounts of oxalates are found in Halogeton glomeratus (halogeton), Sarcobatus vermiculatus (greasewood), Rheum rhaponticum (rhubarb), Oxalis cernua (sournob), and Rumex sp. (Sorrel and dock). Other sources of dietary oxalates include Aspergillus niger and A. flavus; these fungi produce oxalates as a by-product of their metabolism and frequently contaminate feedstuffs. Large doses of ascorbic acid have caused oxalate nephrotoxicosis in humans and a goat. Primary hyperoxaluria is an inherited disorder affecting cats, Tibetan spaniels, and humans. The accumulation of oxalate crystals in the renal tubules also occurs in dogs and cats that ingest ethylene glycol. Horses are resistant to oxalate toxicity but may develop fibrous osteodystrophy fibrosia with chronic ingestion of oxalates.

Hyperoxaluria with supersaturation by calcium oxalate is the most important factor in oxalate urolithiasis; low urine pH increases the severity of the disease. The nephrotoxic effects of oxalate crystals probably involve mechanical damage and obstruction, as well as the chelation of calcium and magnesium. Depletion of these two minerals interferes with oxidative phosphorylation, and results in cellular injury and death.

Contributor: Institute of Animal Pathology, University of Berne, P.O. Box 2735, CH-3001 Berne-Switzerland.

References:

1. Clark EGC and Clarke ML (1967): Veterinary Toxicology, 3rd

el. BailliŠ Tindall & Cassell, London.

2. Cottier H (1980): Pathologenese - Ein Handbuch f

r die „rztliche Fortbildung, vol. 1. Berlin, Heidelberg,

New York: Springer Verlag.

3. Khan SR and Woodard JC (1986): Calcium Oxalate Urolithiasis,

Rat. In: Monographs of Pathology of Laboratory Animals, Eds. Jones

TC, Mohr U and Humt RD. pp 355-361. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York:

Springer Verlag.

4. Maxie MG (1993): The Urinary System. In: Pathology of Domestic

Animals. Eds. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC and Palmer N., vol 2, pp 447-528.

San Diego, New York, Boston, London, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto: Academic

Press, INC.

5. Moeschlin L (1986): Klinik und Therapie der Vergiftungen. George

Thieme Verlag, Stuttgard, New York.

6. Robert N and Allchurch AF (1995): Poisoning of Alaotran gentle

lemur (Hapaleur griseus alaotrensis) by Russian vine (Polygonum

baldschuanicum) at the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust. Verh.Ber.Erkrg.

Zootiere 37:207-210.

7. Teuscher E and Lindequist U (1994): Biogene Gifte. Gustav Fischer

Verlag, Stuttgart, New York.

8. Yanai T et al. (1995): Subclinical renal oxalosis in wild-caught

Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). J. Comp. Path. 112:127-131.

9. Maxie MG: The Urinary system in Pathology of Domestic Animals.

Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, and Palmer N eds. Academic Press, Inc.,

San Diego, 4th ed., vol. 2 pp. 492-492, 1993

Dana P. Scott

Captain, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615

DSN: 662-2615

Internet: Scott@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.