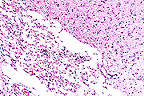

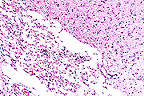

Cavitation necrosis in the

brain of a Maltese (HE, 200X, 126K).

Cavitation necrosis in the

brain of a Maltese (HE, 200X, 126K).Signalment: 5-year-old Maltese terrier canine.

Cavitation necrosis in the

brain of a Maltese (HE, 200X, 126K).

Cavitation necrosis in the

brain of a Maltese (HE, 200X, 126K).

History: Presented 16 months previously with lethargy and neck pain. Clinical signs ameliorated with prednisone treatment. Clinical signs reccurred after 8 months. MRI done at that time revealed cerebral cortical atrophy and areas of chronic and active inflammation, particularly in the occipital cortex. The dog became blind, but was treated with steroids for 5 more months before euthanasia.

Gross Pathology: The cerebral cortex contains multiple areas of cavitation and collapse, with extensive thinning of the cortex.

Laboratory Results: CSF samples examined at presentation revealed WBC= 43 x 109/L, RBC=15 x 1012/L, and protein=31.6 mg/dl.

Morphologic diagnosis: Multifocal cerebral cavitation, with variable lymphoplasmacytic meningoencephalitis and astrogliosis.

Contributor's Comments: Cavitational lesions were distributed within both cerebral cortices, and affected gray matter, white matter, or both. The amount of inflammation is variable between specimens, but most slides have at least a few areas. The clinical course and character of the lesion is suggestive of the necrotizing meningoencephalitis recently described in Maltese dogs. One of the cases described in a case series of this disease had a rather similar relapsing and remitting clinical course.

Gross and microscopic lesions observed in this dog were rather similar to the above mentioned case, with the exception of more extensive cavitation observed here.

AFIP Diagnosis: Cerebrum, white and grey matter: Necrosis, multifocal to coalescing, with myelin loss, gliosis, and mild multifocal lymphoplasmacytic meningitis, Maltese terrier, canine.

Conference Note: Necrotizing meningoencephalitis of Maltese dogs is characterized by bilateral and asymmetrical necrosis and lymphoplasmacytic inflammation of grey and white matter, predominantly in the cerebral hemispheres. There is also lymphoplasmacytic inflammation of the overlying meninges. A similar condition occurs in Pug dogs and is believed to represent the same disease. Similar lesions have also been described in a Shih Tzu and Yorkshire terriers, although the distribution of lesions differs in Yorkshire terriers.

Maltese and Pug dogs suffering from necrotizing meningoencephalitis frequently present with a history of seizures which may or may not be accompanied by other neurologic signs. At necropsy, the brain is often swollen, the demarcation of grey and white matter is obscured, and the ventricles may be asymmetrically dilated. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid may demonstrate nonspecific findings consistent with cerebral disease, including elevated protein levels and white cell counts.

The etiology of necrotizing meningoencephalitis is unknown. Because similar lesions develop in humans infected with human herpesvirus type 1, it has been suggested that a herpesvirus may be the causative agent; however, herpes- virus has not been identified in lesions of necrotizing meningoencephalitis.

Contributor: University of Missouri Dept. Veterinary Pathology, P.O. Box 6811, Columbia, MO 65205.

References:

Stalis IH, Chadwick B, Dayrell-Hart B, Summers BA, Van Winke TJ. Necrotizing meningoencephalitis of Maltese dogs. Vet Pathol 32: 230-235, 1995.

Signalment: Approximately 10-day-old female crossbred pig.

History: Nine pigs between 4 and 11 days of age were submitted from a previously pseudorabies-free herd after an acute outbreak of central nervous system signs. Two sections of a building were affected. The history and clinical signs indicate that the outbreak began at one end of the building and preceded through adjacent litters. Antemortem examination revealed most pigs to be in lateral recumbency, with marked nystagmus and weak padding motions.

Gross Pathology: A range of lesions was observed in the pigs. Multiple white foci were distributed randomly in liver, spleen, and tonsil. Lungs were sometimes edematous. Multiple reddish-gray pinpoint foci were present in all lung lobes. Multiple red pinpoint foci were distributed throughout the renal cortex. Mesenteric edema was present in loops of spiral colon.

Laboratory Results: None submitted.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Colon, colitis, fibrinosuppurative, necrotizing, diffuse to segmental, with mesenteric edema, and intra-epithelial nuclear inclusions. Myenteric plexus, necrotizing neuritis with intra-neuronal nuclear inclusions.

Microscopic lesions vary in appearance among the histological slides.

Colonic sections examined display clumps of fibrin containing cellular debris, bacteria, and inflammatory cells adhered to mucosa segments. Short segments of surface enterocytes are denuded. Crypt epithelial cells are often vacuolated and distorted. Nuclei contain eosinophilic inclusions. Cellular debris and degenerate cells fill crypt lumens. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates broaden areas of the lamina propria. Linear aggregates of inflammatory cells extend along the muscularis mucosa into submucosal areas. Myenteric plexi are often necrotic, with associated neutrophilic infiltrates. Small numbers of nuclei in necrotic and degenerating cells contain eosinophilic inclusions. Multiple foci of necrosis are distributed between muscle layers. Loose connective tissue of mesenteric attachments is broadened by pale eosinophilic edema fluid. Small numbers of vessels are encompassed by mixed to mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates.

Sections of other tissues evaluated display multiple random foci of coagulative to caseous necrosis distributed throughout the liver, spleen, tonsils, and kidneys. Eosinophilic nuclear inclusions are present in all aforementioned tissues within necrotic cells, and cells adjacent to necrotic foci. Severe non-suppurative encephalitis, with neuronal nuclear inclusions, is present.

Fluorescent antibody tests were positive for pseudorabies, as was virus isolation. No bacterial pathogens were isolated from tissues submitted.

Lesions observed in colonic sections are similar to those which have been described in small intestinal sections from young pigs experimentally inoculated with pseudorabies virus. To our knowledge, colonic lesions have not been previously described in the literature.

Pseudorabies (PRV) is caused by a herpesvirus. Disease in natural infection may be characterized by fever, anorexia, and progressive central nervous system signs. PRV most often affects the central nervous system producing typical lesion of non-suppurative meningoencephalitis. Pulmonary, hepatic, splenic, and tonsilar lesions are also frequently observed in naturally occurring cases. Mortality and morbidity are often highest in suckling pigs, moderate in feeder pigs, and lowest in mature animals. High levels of mortality and morbidity may be recognized in all age groups in naive herds.

AFIP Diagnosis: Colon: Colitis, necrotizing, subacute, transmural, diffuse, moderate to severe, with myenteric ganglioneuritis, and intraepithelial and intraneuronal eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies, mixed breed, porcine, etiology consistent with porcine alpha herpesvirus.

Conference Note: Aujeszky's diseases, also known as pseudorabies, is caused by porcine herpesvirus 1 (PHV). All domestic species are susceptible to PHV; however, there are few reports in horses and goats. In addition, cases of PHV infection have been reported in many species of wild mammals, including coyotes, raccoons, rats, mice, rabbits, deer, badgers, and coatimundi. It is not known if these animals play a role in the farm to farm transmission of PHV. Porcine herpesvirus can remain latent in the trigeminal ganglion and tonsil of pigs for over one year and be intermittently shed in nasopharyngeal secretions. The virus also survives for extended periods in the environment, remaining viable for several months in dried tissue.

Porcine herpesvirus is transmitted primarily by direct nose to nose contact, although it may be transmitted by ingestion. Ingestion of infected pig meat is an important source of infection for dogs and cats. Initial viral replication occurs in the epithelium of the oropharynx. The virus then spreads along the olfactory, glossopharyngeal, or trigeminal nerves to the brain. A viremia develops which disseminates the virus to many organs where the virus replicates in vascular endothelium, lymphocytes, and macrophages. Percutaneous inoculation of PHV induces a serofibrinous inflammatory reaction at the site. The virus spreads from the site of inoculation centripetally along peripheral nerves to the spinal cord, then outward along other peripheral nerves as other segments of the spinal cord are involved. Transplacental infection also occurs in swine causing abortion or mummification of fetuses.

Clinical signs in swine are varied and dependant upon the age and immune status of the infected animal. Neonatal and weaner pigs are very susceptible to PHV and may have a high mortality rate. Neonates become prostrate and die quickly, often without nervous signs. Slightly older animals develop signs of nervous system involvement including incoordination, twitching, paddling, convulsions, and death. Aujeszky's disease in older pigs is characterized by fever, respiratory signs, and abortion. In animals other than pigs, the disease is usually fatal. Clinical signs include fever and intense pruritus. Neurologic signs are variable but always present to some degree.

Histologically, PHV causes a nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis and paravertabral ganglioneuritis; the grey matter is most severely affected. There are intranuclear inclusions in astrocytes and neurons. Other lesions commonly seen include rhinitis, pulmonary edema, necrotizing enteritis, and multifocal necrosis of the spleen, lung, liver, tonsil, lymph nodes, and adrenal glands. In cases of PHV-induced abortion, there is endometritis and necrotizing placentitis with intranuclear inclusions in trophoblasts.

Contributor: Veterinary Diagnostic Center, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68583-0907.

References:

1. Narita M, Kubo M, Fukusho A, et al: Necrotizing Enteritis in

piglets associated with Aujeszky's disease virus infection. Vet

Pathol 21:450-452, 1984.

2. Olander HJ, Saunders JR, Gustafson DP, Jones RK: Pathologic findings in swine affected with a virulent strain of Aujeszky's virus. Path Vet 3:64-82, 1966.

3. Fenner FJ, Gibbs EPJ, Murphy FA, Rott R, Studdert MJ, White DO: Veterinary Virology. Academic Press, INC., San Diego, 2nd edition, pp. 351-354, 1993.

4. Jubb KVF, Huxtable CR: The nervous system in Pathology of Domestic Animals. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N eds, Academic Press, INC., San Diego, 4th edition: pp. 406-409, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #3127, 3230-1, 4259, 4579-80, 5152-56, 5200, 10132, 20459-64, and 23199.

Signalment: Three-day-old male Holstein calf.

History: Shortly after birth, the calf was given 1 pint of colostrum and a colostrum supplement by oral intubation. The calf nursed well for one day. On the second day the calf was depressed and not nursing. It was given electrolytes by oral intubation. The calf developed a large swelling from the mandible to the thoracic inlet and was euthanatized.

Gross Pathology: The subcutis of the ventral head, neck, thorax and cranial abdomen was thickened (0.5 to 5 cm) with a gelatinous fluid with numerous gas pockets.

Laboratory Results: Fluorescent antibody evaluation of subcutis was negative for Clostridium chauvoei but positive for Clostridium septicum.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Morphologic diagnosis - Skin/subcutis of neck - severe acute serofibrinous, hemorrhagic and suppurative cellulitis and dermatitis with necrosis, emphysema, necrotizing vasculitis and intralesional bacteria. Cause - Clostridium septicum.

Etiologic diagnosis - clostridial cellulitis/dermatitis.

Name of the disease - malignant edema.

No lesions were found in the esophagus or pharynx to relate the malignant edema to the intubations. The initiating factor for the disease was not determined.

AFIP Diagnosis: Haired skin and subcutis of neck (per contributor): Cellulitis, necrotizing, acute, diffuse, severe, with necrotizing vasculitis, edema, hemorrhage, emphysema, and gram-positive bacilli, Holstein, bovine, etiology consistent with Clostridium sp.

Conference Note: Malignant edema is caused by wounds that become infected with bacteria of the genus Clostridium, the most common species being C. septicum, C. perfringens, C. novyi (swelled head in rams), and C. chauvoei. Clostridia are gram-positive, spore-forming bacteria that are ubiquitous in the environment. These bacteria require anaerobic conditions and an alkaline ph to grow. These specific requirements frequently occur as a consequence of deep, penetrating wounds. Horses, ruminants, and pigs are very susceptible to cutaneous clostridial infections; cats and dogs are more resistant.

Malignant edema is typically a cellulitis characterized by severe edema, crepitation, discoloration of overlying skin, and signs of systemic toxemia (prostration, circulatory collapse, and sudden death). Histologically, there is a necrotizing cellulitis and vasculitis, with edema, emphysema, and hemorrhage at the site of bacterial inoculation. The lungs are severely congested and there are often signs of toxic degeneration in other parenchymatous organs. Death in affected animals is due to systemic intoxication.

Clostridium septicum is the most common cause of malignant edema in animals. Clostridium septicum produces four major exotoxins: alpha, beta, delta, and gamma. Alpha toxin is a lecithinase which is necrotizing and hemolytic. Beta toxin is a deoxyribonuclease and is leukocidal. Delta toxin is a hyaluronidase, and gamma toxin is a hemolysin. Dispersion of the bacteria and these exotoxins is facilitated by bacterial production of gas and the formation of edema, which separates surrounding tissues along facial planes. The lesion develops quickly and death may occur within 24 hours of the onset of clinical signs.

Clostridium septicum is also responsible for braxy, a necrohemorrhagic abomasitis and toxemia of sheep.

Contributor: The Ohio State University, Dept. of Veterinary Biosciences, 1925 Coffey Rd, Columbus, OH 43210-1093.

References:

1. Hulland, T.J. Muscle and Tendon. In: Jubb, K.V.F., Kennedy,

P.C., Palmer, N, (eds). Pathology of Domestic Animals, fourth

edition, volume 1, chapter 2, pp. 245-247, Academic Press, San

Diego, 1993.

2. Radostits, O.M., Blood, D.C., and Gay, C.C. Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Disease of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses, eighth edition, BailliŠre Tindall, London, PP. 686-688, 1994.

3. Timoney JF, Gillespie JH, Scott FW, and Barlough JE: Hagan and Bruner's Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals. Comstock Publishing Associates, 8th edition, pp. 236, 1988.

Signalment: Three-month-old male castrate domestic sheep.

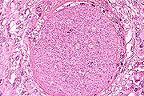

Megaloschizont of Eimeria

sp. in the lymph node of a 3-month-old lamb. (HE, 400X, 113K)

Megaloschizont of Eimeria

sp. in the lymph node of a 3-month-old lamb. (HE, 400X, 113K)

History: A flock of 1,300 ewes and lambs on a high mountain summer range was observed by the herder to have 40-50 lambs that were lame, walked with slightly stiff rear legs and often were reluctant to move. A live 3-month-old lamb was submitted to the veterinary diagnostic laboratory for evaluation. The clinical signs were as described.

Gross Pathology: Necropsy displayed increased cloudy synovial fluid in the coxofemoral and stifle joints with fibrin plaques present in the joint spaces. The synovial membranes were slightly thickened and there was extensive edema in the muscle septa along the tendon sheaths distal to the stifle joints. The mesentery of the jejunum was extremely edematous and the mesenteric nodes were enlarged.

Laboratory Results: Chlamydial agents were cultured from the joint lesion material in developing chick embryos. There were no microbial agents cultured from the mesenteric nodes.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Mesenteric lymph node: Lymphoid hyperplasia and cortical granulomatous areas containing giant schizonts. Lymphangitis, granulomatous with multiple giant schizonts, occasional schizonts are mineralized - Eimeria ovinoidalis.

The lymph node alterations were incidental to the chlamydial polyarthritis. Large schizonts are occasionally found incidently in the submucosal lymphatic vessels and in the cortical or medullary sinusoids of mesenteric lymph nodes (where they elicit a granulomatous reaction). Rarely do coccidial gametocytes or oocysts develop in the nodes.

These stages probably result from establishment of sporozoites or primary merozoites that are carried from the lacteal into the lymphatic drainage early in an infection. Development in these areas in aberrant and probably dead end.

AFIP Diagnosis: Lymph node: Lymphadenitis and lymphangitis, granulomatous, multifocal, moderate, with paracortical lymphoid hyperplasia and numerous coccidial megaloschizonts, breed unspecified, ovine.

Conference Note: This case was reviewed by Dr. C.H. Gardiner, parasitology consultant for the Department of Veterinary Pathology, AFIP. The megaloschizonts contain whorls of elongate merozoites whose nuclei are arranged in circular blastophores. The species could not be positively identified; however, it does belong to the genus Eimeria. Approximately a dozen species of coccidia have been identified in sheep, many of which are capable of producing megaloschizonts. Eimeria ovinoidalis is one of these.

Eimeria ovinoidalis is transmitted by ingestion of sporulated oocysts. Eimerian oocysts have 4 sporocysts that contain 2 sporozoites each. After ingestion the sporozoites are released from the oocyst in the small intestine. Sporozoites of E. ovinoidalis penetrate into the lamina propria of the distal ileum where they produce giant first-generation schizonts. Merozoites produced in these schizonts are then released, where they invade epithelial cells of the distal ileum, cecum, and colon. The merozoites develop into second-generation schizonts (again releasing merozoites that infect adjacent epithelial cells), or they undergo gametogony. After fertilization of macrogamonts (female) by the microgamonts (male) unsporulated oocysts are formed and passed in the feces. The oocysts sporulate in the environment and are then infective to susceptible hosts.

Eimeria ovinoidalis is commonly encountered in feedlot lambs. Lesions are limited to the distal ileum, cecum and colon, and are associated with second-generation schizogony and gametogony. Affected lambs develop diarrhea, then become dehydrated, acidotic, and hypoproteinemic. Histologic lesions are similar to those in cattle infected with E. bovis (see Wednesday Slide Conference 2, case I, 1995).

Contributor: Utah State Laboratory, Utah State University, 950 East 1400 North Logan, Utah 84322-5700.

References:

1. Gardner, C.H., Fayer, R. and Duby, J.P. An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissue. USDA, ARS, Agricultural Handbook, Number 651.

2. Jubb, K.V.F., Kennedy P.C., and Palmer N. Pathology of Domestic Animals, Third Edition, Vol. 3. Academic Press Inc. 1985.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #4049, 4839, 5062, 9692, 9693, and 22777.

Dana P. Scott

Captain, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: Scott@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.